Deliver simulation at scale with Oxford Medical Simulation

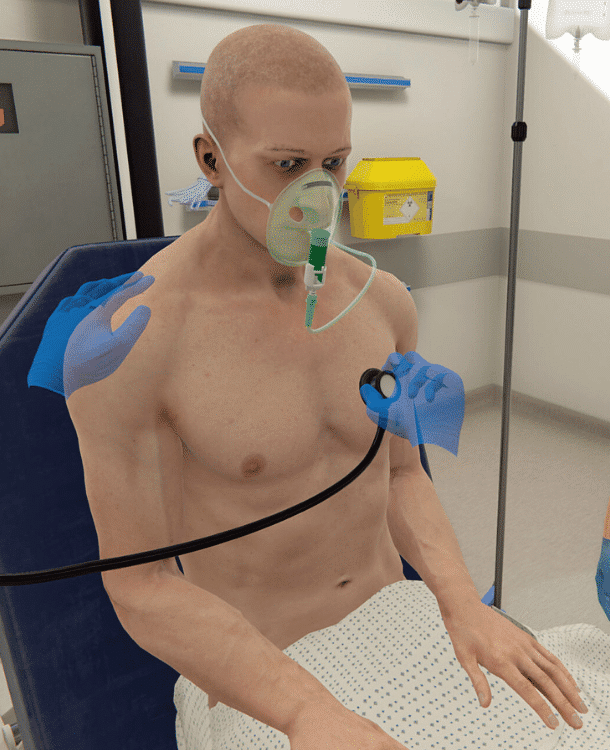

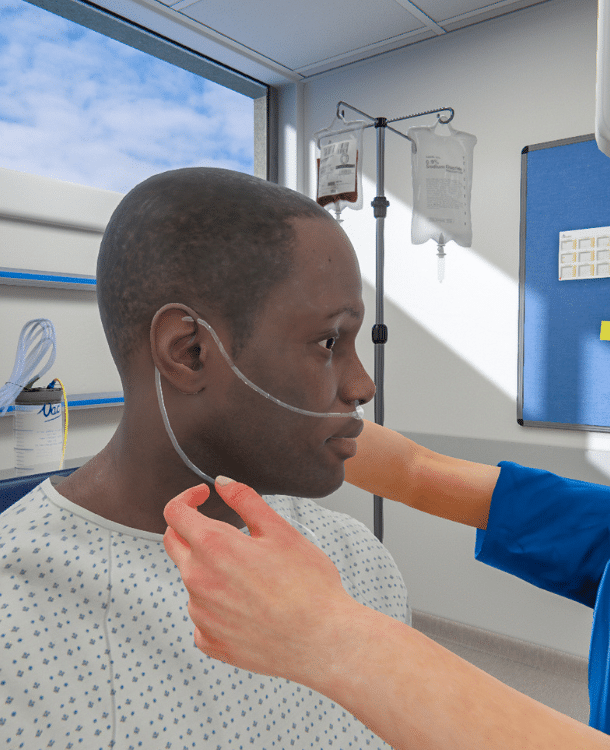

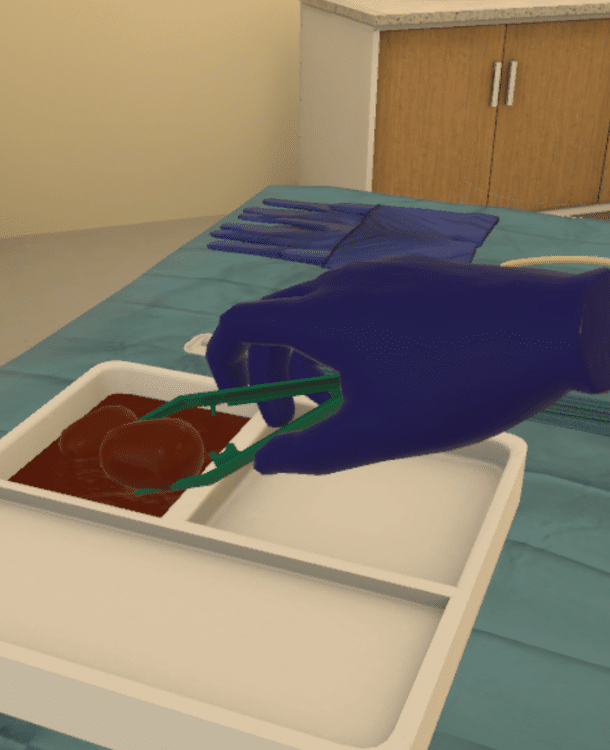

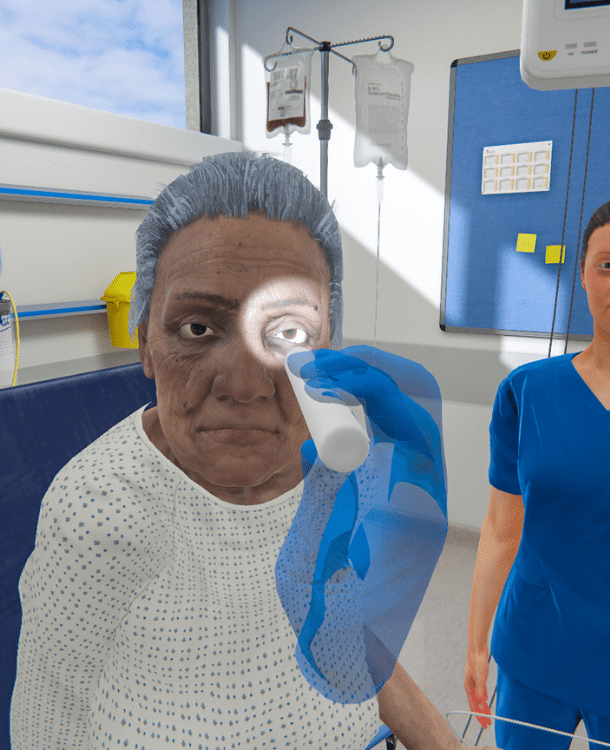

Combining healthcare education and competency assessment with dynamic VR simulations

Created by experts,

backed by evidence

A powerful learning platform bridging theory with immersive scenarios - offering in-depth insights into clinical performance

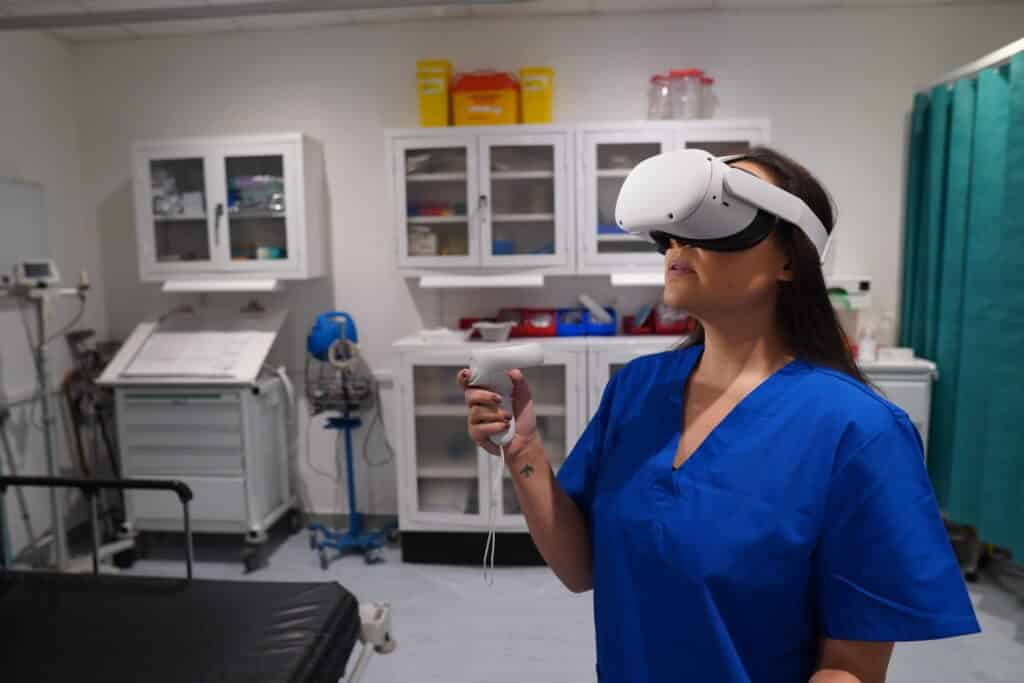

Practice anytime, anywhere

On the unit, in the classroom, or at home – OMS you can take anywhere.

Self-directed and facilitated

Practice solo for self-paced learning or with expert educators and your team to maximize collaboration.

In VR and on screen

Use virtual reality headsets for ultimate immersion, or deliver on screen to ensure accessibility at scale.

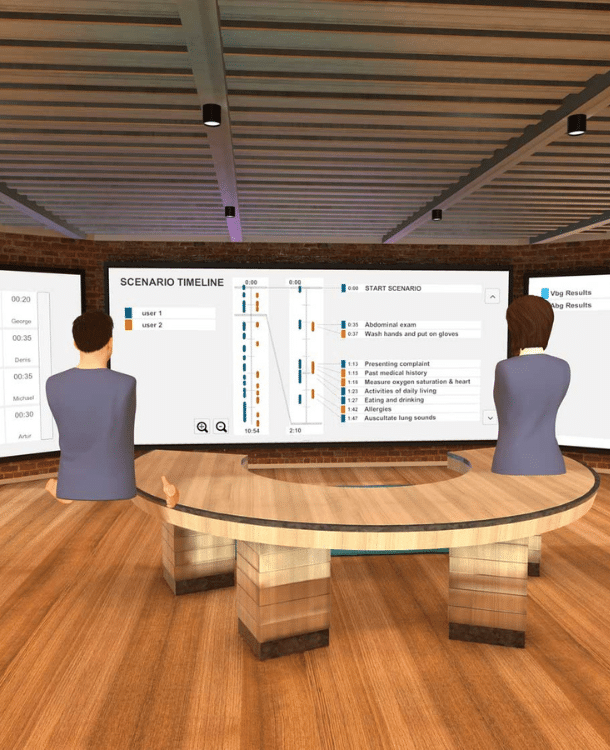

Adaptive and standardized

Provide dynamic clinical experiences on-demand, with objective measures of competence to optimize performance.

Practice anytime, anywhere

On the unit, in the classroom, or at home – OMS you can take anywhere.

Self-directed and facilitated

Practice solo for self-paced learning or with expert educators and your team to maximize collaboration.

In VR and on screen

Use virtual reality headsets for ultimate immersion, or deliver on screen to ensure accessibility at scale.

Adaptive and standardized

Provide dynamic clinical experiences on-demand, with objective measures of competence to optimize performance.

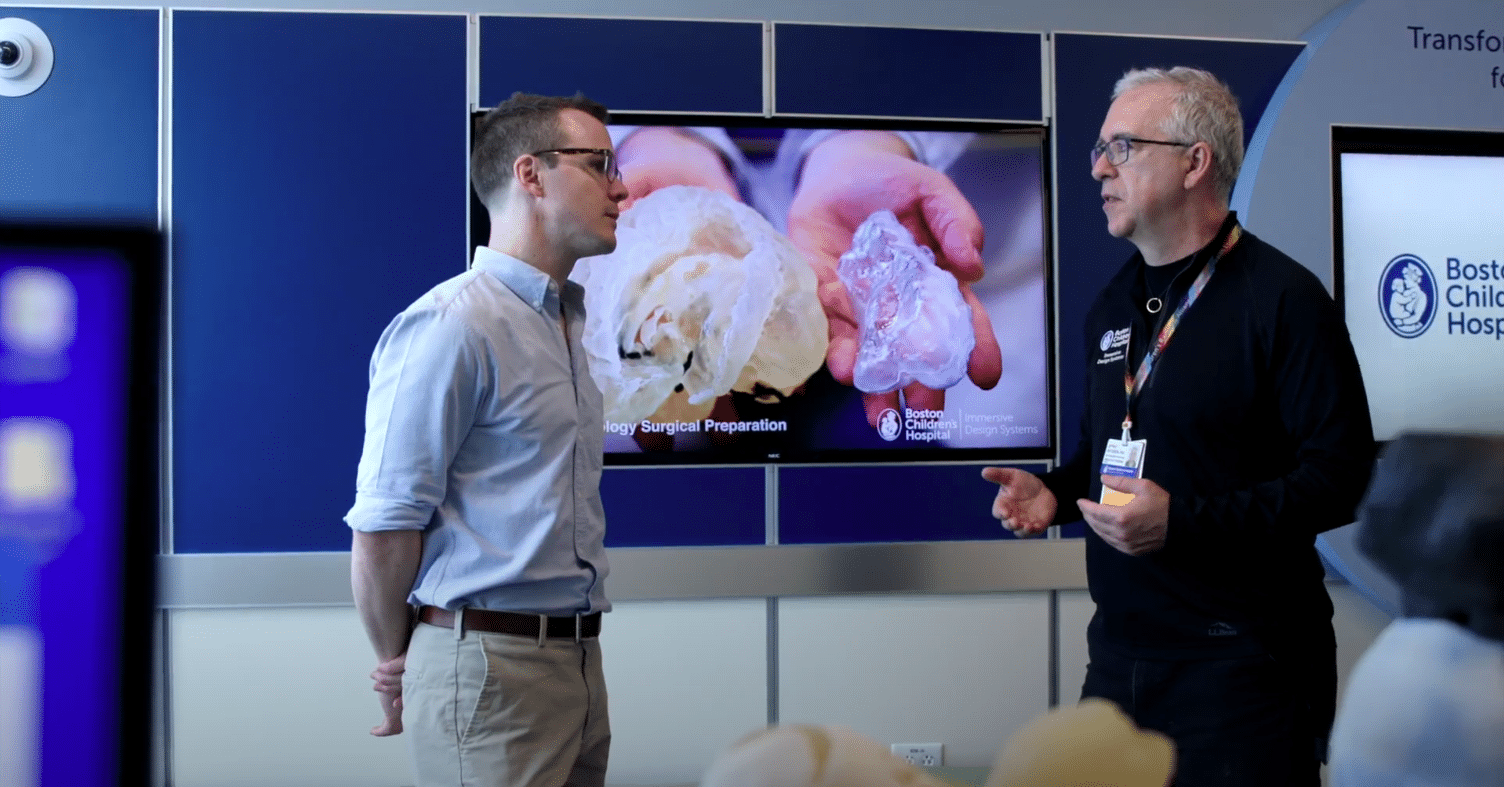

Our trusted partners

World-leading institutions use OMS to scale clinical education, training, and assessment across nursing, medicine, and allied health.

Why OMS?

Depth, breadth, data, and expertise combine to deliver simulation and competency assessment at scale.

Tailored learning solutions

Diverse methods of engagement to support learners in any situation

Build skills, reduce costs

Prepare learners for practice while reducing time, effort, and equipment costs.

OMS in Healthcare Systems

Our platform helps systems:

- Recruit

- Onboard

- Train & assess

- Upskill & reskill

- Support & retain

- Reduce costs

OMS in Academic Institutions

Our platform helps institutions:

- Scale clinical placements

- Map & track competency

- Standardize feedback

- Eliminate bias in assessment

- Reduce pressure on faculty

- Reduce costs